INIMBY DELLA SHOAH: 'FERMATE I LAVORI PER IL MUSEO"

LA BORGHESIA ROMANA DI VIA TORLONIA, SPAVENTATA DALLE SCRITTE PRO PAL, INVIA UN ESPOSTO AL CAPO DELLA POLIZIA: "SPOSTATE IL MONUMENTO"

Roma. "Fermare i lavori per la realizzazione del museo Shoah".

Non lo chiede un gruppo impazzito di antisemiti, un collettivo di stu-denti o pro Pal o qualche sigla neo nazista. Niente di tutto questo. An-zi. La richiesta arriva dall'alta e media borghesia illuminata di un pezzo della capitale, spaventata

dall'eventualità che la nuova strut-tura - un progetto che ha atteso oltre vent'anni per diventare real-ta - possa rendere il loro amato quartiere meno sicuro. Viviamo in uno "stato di incessante minaccia e allerta dall'apertura del cantie-re".

denunciano. Le preoccupazio-ni di questa piccola ma importante porzione di città infatti sono state riassunte all'interno di un esposto che lo scorso 8 marzo è stato invia-to al capo della polizia Vittorio Pi-sani, al questore di Roma Roberto Massucci e, per conoscenza, anche al comune. Sono i residenti di via Alessandro Torlonia, uno dei tre lati del cosiddetto triangolo verde, un'area signorile fatta di villette di pregio, alberi e sobrio lusso a po-chi passi da Villa Torlonia. Quella che fu la residenza di Benito Mussolini si appresta infatti a ospitare il museo per ricordare l'Olocausto.

Ma la memoria spaventa i bene-stanti residenti che invitano la pubblica sicurezza a fermare

il

cantiere e "rivalutare la localizza-zione in altra zona meno popola-. Sono insomma i nimby della Shoah. Ricordare? Assolutamente necessario, ma non sotto casa mia. perché, spiegano: "Dall'apertura del cantiere per la costruzione del museo sono accaduti alcuni eventi intimidatori che stanno compro-

mettendo in maniera significativa

la

sicurezza

dei

sottoscritti"

L'esposto è corredato da un centi-naio di firme. Professori universi-tari, dirigenti pubblici, avocati di grido e giornalisti. Tra loro c'è Augusto D'Agostino, già vicepresi-dente di Unicredit e oggi capo della gestione delle attività e della passivita di Cdp, l'editorialista

Il progetto del Museo della Shoah ha 20 anni, finalmente sono partiti i lavori (foto Ansa)

della Stampa Marcello Sorgi e sua moglie, la costituzionalista Anna Chimenti Caracciolo. C'è poi Fer-dinando Emanuele, avocato par-tner di uno dei più importanti stu-di legali della capitale, BonelliE-rede, la commercialista Delfina

Pricolo, che siede dentro il colle-g10 sindacale della partecipata

della regione, Lazio Crea, la diri-gente del Viminale Paola Nusca, ma anche lo scienziato dell'Esa Luca Conversi e la ballerina Gior-gia Calenda, nessun imparenta-mento pare con il leader di Azione

Carlo

Са-

lenda.

Nel do-cumento

vengono

elencate le

azioni

che

stanno spa-ventando i residenti.

Il

riferi-mento è so-prattutto a

una

serie

di "seritte, messagg1 di odio e

minacce" che sono apparse nella

via

dall'inizio

del cantiere.

Nell'esposto ne sono citate diver-

"Assassini, infami"

"Gaza

45.000 morti", "Fermare il Genoci-dio a Gaza". Scritte che, si legge nella missiva inviata al capo della polizia "con il tempo sono diventa-te sempre più frequenti e violen-te".

Tanto da portare gli abitanti di Via Torlonia anche a suggestionar-si un po': "Alcuni dei messaggi sembrano essere scritti con il san-gue", serivono nell'esposto prima di tornare alla realta e precisares

"Anche se verosimil-

antial sekre e Facole moment

mente ven-gono attua-ti

con

smalto ros-so".

Ma

a

preoccupa-re

SO-

prattutto

Ная доати хорез по ривками, і вокасосоа койсожне во мія, ресторное бе вепреякіс

ecuelase del terod el colioaslace del Mepoo la cgiane del gent nevivi illustrat in

che accan-

prarrodendo ello egonaratte del marrecenne le aare dece eese Problems *

to

alle

scritte pro

Pal.

nel

tempo, ne

Tra i firmatari dell'esposto avvocati, professori, dirigenti pubblici e giornalisti

sono spun-tate

altre

"in colore blu a favore dell'accele-razione dei lavori del museo in cui invitavano il sindaco a concludere il prima possibile i lavori". Insom-ma la paura è che il museo possa diventare l'arena per una versione teppista e capitolina del conflitto mediorientale. Visto quanto acca-duto lo scorso anno tra brigata ebraica e pro Pal il 25 aprile non sarebbe certo una novità. "La sola affissione del cartello del cantiere ha innescato un duro confronto tra

denunciano

quindi gli abitanti di Via Torlonia, finendo perfino per sentirsi discri-minati. Ricordano infatti che per ragioni di sicurezza è stato sposta-to dalla stessa zona l'asilo israelia-no: "Se è stato deciso di spostarlo vuol dire che è stato rilevato un pericolo per la sicurezza pubblica.

Se è così, non si comprende per-ché non si è fatto altro per tutelare la sicurezza di tutti gli altri cittadi-ni. Ravvisiamo una forte discrimi-nazione nella tutela: la sicurezza pubblica va tutelata in favore di chiunque, a prescindere dall'ap-partenenza a una comunità piutto-sto che a un'altra". Insomma per-ché i bambini ebrei sì e noi no? La paura arriva addirittura a far te-mere attentati. "Si temono atti ter-roristici che potrebbero danneg-giare il museo e gli edifici limitrofi che sono a una distanza ravvicina-tissima". E' questo, secondo i de-nuncianti, un punto cruciale. "Il museo - dicono - sara sempre un

obiettivo sensibile". Da persone

raftinate e che conoscono il mondo citano dunque quanto accadrebbe negli altri paesi per motivare la necessità di spostarlo: "A Berlino è stato realizzato al centro di una enorme piazza ben lontana dagli edifici, a Washington sorge sulle sponde del fiume Potomac, ben lontano dalla zona abitata, allo

stesso modo anche quello di Lon-dra è situato nella Zona di Waterloo al centro di un enorme terreno spianato".

Gianluca De Rosa

venerdì 25 aprile 2025

Italia Nostra: Museo della Shoah di Roma: si faccia presto, si faccia bene, si faccia altrove

31 Marzo 2025

Italia Nostra Roma segue con viva preoccupazione la ripresa dei lavori di sbancamento alle spalle della Casina delle Civette di Villa Torlonia, nel lotto che il Comune di Roma ha destinato alla costruzione del "Museo della Shoah".

Italia Nostra Roma torna a chiedere a tutte le istituzioni coinvolte di prendere seriamente in considerazione la possibilità di una sua diversa ubicazione.

Le risultanze delle indagini archeologiche e geologiche sconsigliano ogni ulteriore intervento nell'area delicatissima di Villa Torlonia dove il terreno presenta un complesso sistema di cavità sotterranee ed una falda che non deve essere "disturbata". Tutto ciò è ben noto da tempo a Roma Capitale.

Non possiamo non esprimere le nostre perplessità anche sulla eccessiva vicinanza del Museo alla Casina delle Civette, con conseguente compromissione della sua prospettiva. La rottura dell'equilibrio paesistico di Villa Torlonia toglierebbe respiro e prestigio anche allo stesso Museo, che si troverebbe sostanzialmente interrato.

L'area scelta per la realizzazione del Museo appare problematica anche per ragioni di mobilità: la strada limitrofa è troppo piccola per accogliere i numerosi visitatori, parte dei quali, verosimilmente, verranno trasportati con bus turistici, e la presenza della falda ha comportato un ridimensionamento del parcheggio interrato previsto nel progetto originario.

Roma merita il suo Museo della Shoah, atteso ormai da troppi anni.

Un segno architettonico di tale forza, nella cui forma è inscritta la sua potenza evocativa, pretende la migliore visibilità e accessibilità nella città di Roma.

Il fatto stesso che non sia stato realizzato a più di vent'anni dalla sua ideazione, dimostra oltre ogni ragionevole dubbio che l'area di Villa Torlonia non è adatta.

Per questo ci chiediamo perché si insista a volerlo costruire in un luogo inadeguato, in un buco nel terreno, nel quale sarebbe praticamente invisibile e difficilmente raggiungibile.

roma@italianostra.org

lunedì 14 aprile 2025

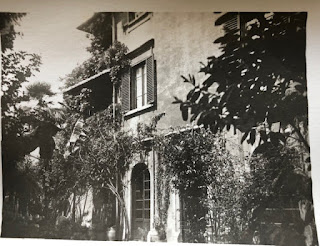

Cosa c’era all’angolo tra via Torlonia e via de Rossi

Queste sono le foto della splendida villa che era posizionata all'angolo fra GB de Rossi già via Pietralata e via Torlonia (via aperta negli anni 20 del secolo scorso ) Villetta del seicento demolita in un giorno nel 1950.

Il nome della proprietà era Cesanelli, forse un cardinale.

Il nome della proprietà era Cesanelli, forse un cardinale.

venerdì 4 aprile 2025

Outcry over plan to build Holocaust museum at Mussolini’s villa

Italy's leading heritage group is pushing for a new site for the museum as construction begins in the Villa Torlonia after 20 years

March 17 2025, 2.56pm GMT

Plans for the museum at the Villa Torlonia have been in the pipeline for two decades. The estate, set in sprawling gardens, features an opulent theatre, a spacious greenhouse adorned with Moorish designs and a "Swiss cabin" known for its stained-glass windows depicting flowers, owls and natural scenes.

Oreste Rutigliano, president of the Rome branch of Italia Nostra, argued that the museum's futuristic design clashed with the surrounding architecture, that its location was too hidden and that nearby streets were too narrow for tourist buses. He also cited a September 2023 survey that revealed underground cavities and a high water table, leading to concerns about land stability.

"We vehemently oppose this project," Rutigliano said. "We have opposed it for 20 years."

Mussolini rented the villa from Giovanni Torlonia in 1925 for a nominal annual fee of one lira — less than a cent in today's money. It remained his official residence for 18 years, during which he built two air-raid shelters on the site and hosted dignitaries, including Mahatma Gandhi in 1930, in its ballroom.

Benito Mussolini with his children at the villa in 1935. He lived there until he was ousted in 1943

FIRESHOT/UNIVERSAL IMAGES GROUP/GETTY IMAGES

Jewish underground cemeteries were discovered beneath the Villa Torlonia during excavations in 1918.

Rome's city council first announced plans for the museum in 2005, but construction has been delayed by administrative hurdles, proposals to relocate it to the Fascist-era EUR neighbourhood in the south of the city and the pandemic. The project gained momentum two years ago when Giorgia Meloni's government allocated €10 million for its construction.

The villa's association with Mussolini — who introduced racial laws in 1938 excluding Jews from certain professions and intermarriage, before the Nazi puppet Italian Social Republic deported Jews to death camps — makes it a potentially powerful location for the museum.

The greenhouse adorned with Moorish designs. Below, the ballroom

ALAMY

However, local residents have long opposed the project. "We've been fighting to preserve the villa from real estate developers for 50 years, well before anyone wanted to build the museum," said Dario Quintavalle, a local.

In response to concerns about land stability, about 50 residents challenged the project in court. Some also expressed fears that the site could attract crime after pro-Palestinian graffiti and excrement were smeared on construction cabins last month.

The court ultimately approved the project after the city council submitted documents proving the land's stability. A council spokesman said: "Work resumed after the court's decision, but the council is ready to listen to Italia Nostra's concerns."

Rutigliano suggested relocating the museum to a more symbolically significant and accessible site, such as Tiburtina railway station, where an installation marks the platform from which Jews were deported to Auschwitz in 1943.

He said: "I understand that after 20 years, finding another location is difficult, but we will continue to push for it while we still can."

Dario Quintavalle

March 17 2025, 2.56pm GMT

Plans for the museum at the Villa Torlonia have been in the pipeline for two decades. The estate, set in sprawling gardens, features an opulent theatre, a spacious greenhouse adorned with Moorish designs and a "Swiss cabin" known for its stained-glass windows depicting flowers, owls and natural scenes.

Oreste Rutigliano, president of the Rome branch of Italia Nostra, argued that the museum's futuristic design clashed with the surrounding architecture, that its location was too hidden and that nearby streets were too narrow for tourist buses. He also cited a September 2023 survey that revealed underground cavities and a high water table, leading to concerns about land stability.

"We vehemently oppose this project," Rutigliano said. "We have opposed it for 20 years."

Mussolini rented the villa from Giovanni Torlonia in 1925 for a nominal annual fee of one lira — less than a cent in today's money. It remained his official residence for 18 years, during which he built two air-raid shelters on the site and hosted dignitaries, including Mahatma Gandhi in 1930, in its ballroom.

Benito Mussolini with his children at the villa in 1935. He lived there until he was ousted in 1943

FIRESHOT/UNIVERSAL IMAGES GROUP/GETTY IMAGES

Jewish underground cemeteries were discovered beneath the Villa Torlonia during excavations in 1918.

Rome's city council first announced plans for the museum in 2005, but construction has been delayed by administrative hurdles, proposals to relocate it to the Fascist-era EUR neighbourhood in the south of the city and the pandemic. The project gained momentum two years ago when Giorgia Meloni's government allocated €10 million for its construction.

The villa's association with Mussolini — who introduced racial laws in 1938 excluding Jews from certain professions and intermarriage, before the Nazi puppet Italian Social Republic deported Jews to death camps — makes it a potentially powerful location for the museum.

The greenhouse adorned with Moorish designs. Below, the ballroom

ALAMY

However, local residents have long opposed the project. "We've been fighting to preserve the villa from real estate developers for 50 years, well before anyone wanted to build the museum," said Dario Quintavalle, a local.

In response to concerns about land stability, about 50 residents challenged the project in court. Some also expressed fears that the site could attract crime after pro-Palestinian graffiti and excrement were smeared on construction cabins last month.

The court ultimately approved the project after the city council submitted documents proving the land's stability. A council spokesman said: "Work resumed after the court's decision, but the council is ready to listen to Italia Nostra's concerns."

Rutigliano suggested relocating the museum to a more symbolically significant and accessible site, such as Tiburtina railway station, where an installation marks the platform from which Jews were deported to Auschwitz in 1943.

He said: "I understand that after 20 years, finding another location is difficult, but we will continue to push for it while we still can."

Dario Quintavalle

Iscriviti a:

Commenti (Atom)